No Fixed Form (2/2)

What do we learn from plasticity?

This is the follow up to the last article. As before, it is adapted from a talk given at RHS Pride in Nature on 7th September.

In the last post we looked at plasticity in the plant kingdom, so lets work our way through the shrub of life and take a look at Protista. This kingdom of life is defined by being single-celled organisms that have a single nucleus. Whenever someone talks about amoebae, they’re talking about protists.

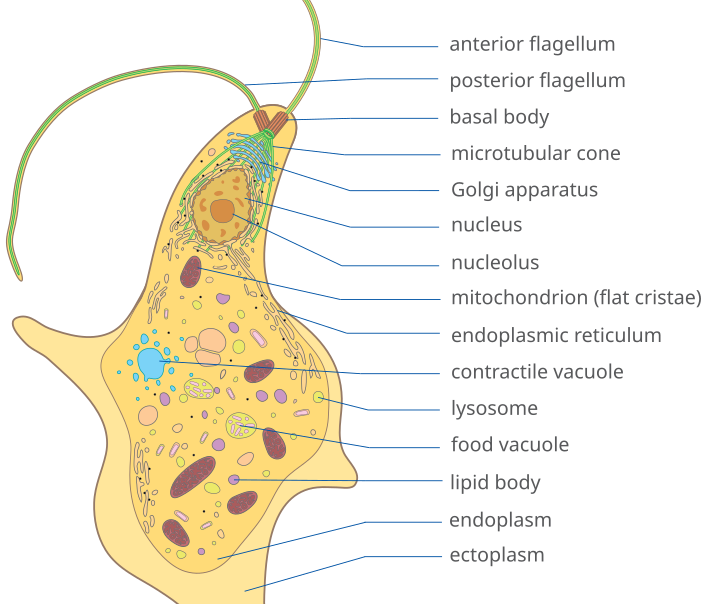

This is a kind of slime mould, a myxomycete, or myxogastrid, depending on who your taxonomic daddy is. Myxomyxetes are able to spend most of their time as a microscopic single-celled organism. They can even kind of dry themselves out in cysts to live longer if the world gets too dry, or grow a little tail (flagella) to propel themselves around if its really wet. What’s really interesting, however, is what happens when they cross-fertilise.

When two cells meet in their active phase, they fuse into one and cross-fertilise (a process called Zygogenesis), then start to divide their nuclei into new nuclei. But they do this without building new cells. Instead, the size of the cell just increases, consuming other organisms around it - we call this huge cell a plasmodium. If you’ve seen Akira, it’s a bit like the scene at the end where Tetsuo can’t stop growing (don’t look it up if you’re squeamish). So despite being able to grow to between 1 and 5 metres squared in size, these are still unicellular organisms, just with millions of nuclei, Through sex, or more accurately cross-fertilisation, the tiny has become huge.

Why do they do this? Probably in response to some environmental pressure, a lack of food. Perhaps becoming a plasmodium offers a risky, all-in strategy to survive hard times.

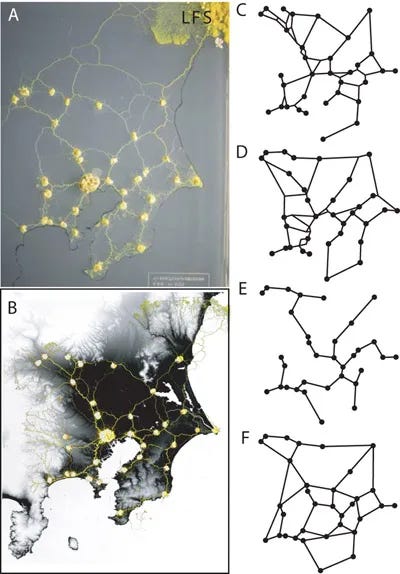

Researchers have attempted to better understand the capabilities of plasmodium with experiments designed to test how they respond to mazes and resource scarcity. In a now-famous experiment, a Myxomycete plasmodium, Physarum polycephalum was evaluated for its ability to build an efficient network in a recreation of the Tokyo railway network, with each town represented as a node of oats. The Physarum was not only able to imitate the map of the rail network, but actually recreate it more efficiently.

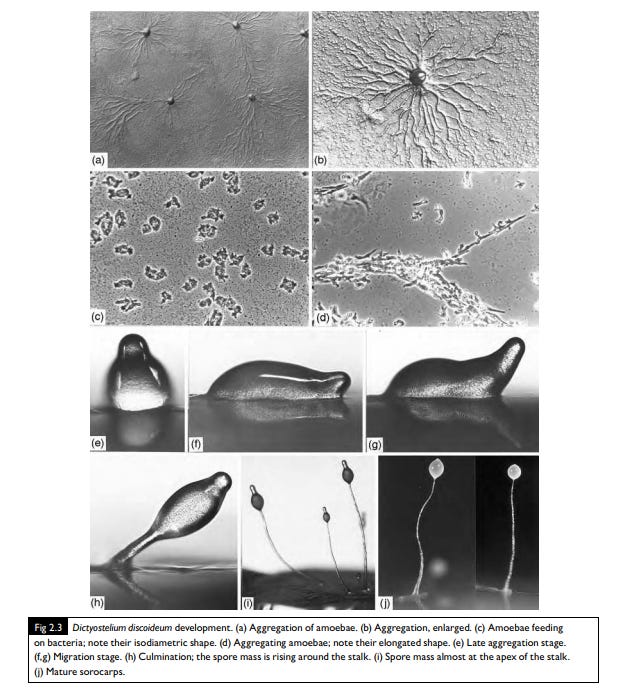

There’s also another group of slime moulds that really trouble our idea of individuals. Dictyostelium discoideum (sadly no common name that I know of, but perhaps you can come up with one) isn’t just the megaproject of two individuals, but countless thousands. Through chemical signalling, these microscopic amoeba are able to form the slug-like forms you can see above, which then ascend into reproductive tower-like structures called sorocarps. Reproduction then becomes a kind of lottery, in that whichever individuals end up on top are the lucky few that get to send spores out in to the wind, to take a punt at life elsewhere. But are they individuals cheating the system, or just part of the whole? Our sex cells are actually different from our lung cells, yet do we ever consider them not to be us? Are they individuals, or a meta-organism? Why not both?

Schizophyllum commune, the Split Gill mushroom, has generated a degree of notoriety in queer ecology for having 22,960 mating types. A mating type might be considered as roughly analogous to sex in animals. I think that, as queer people, its understandable that we often look for reflections of our diversity in nature, especially in response to being deemed and derided as un-natural by society. I understand that reflex, but I think we need to be careful that we don’t let a desire to see our identities mirrored in other species stop us from asking more fundamental questions about how these behaviours suggest fungi relate to each other and their environment.

However, the idea of a Venn diagram of sexual compatibility for 22,960 mating types is interesting, because it raises the kind of questions I don’t think that mycology has been able to answer yet. (Please, correct me if I’m wrong and there is a paper that explains it.)

Why? What is the benefit? It’s fair, I think, to assume that its because it works on some level. It gives options, choices on how to live. And we need to be humble and realise that fungi is literally the foundation for all life on land, a lineage of life that has been around for 2400 million years. For context that’s 10 times older than Ginkgo biloba and 1200 times older than Homo, so they must have a fairly good handle on survival strategies.

We can also see fungi choose different methods of reproduction quite easily in our back gardens.

Xylaria hypoxylon, aka Candlesnuff fungus, is asexual in the Spring and Summer and sexual in the Winter. The colours of the asexual spores are light and the sexual ones are dark, hence you can see what kind of sex they’re doing just by looking at them.

The challenge of this talk is to narrow down the countless ways that different species are plastic in a way that helps illustrate something more fundamental about life in general. There are countless more examples and it would take a book to cover them. But let’s not neglect the animal kindom. And while I think we’re all aware of the incredible metamorphoses of caterpillars into butterflies, (trans people do love butterflies) it is this next species that really activates my wonder.

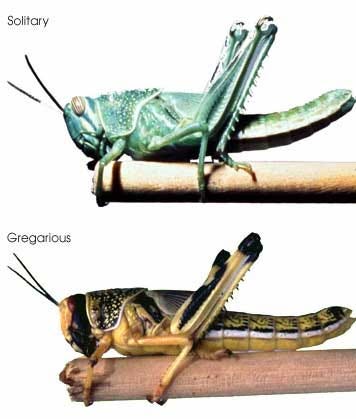

For a long time we didn’t understand where locusts came from, which I think helps understand why their appearance felt like so much divine retribution. They are, we now know, the same species as grasshoppers, transforming in response to food shortages. Grasshoppers, e.g. Schistocerca above, are able to activate a different set of genes and transform their body into a new, sort of orgy slash rave form that enables them to travel and function effectively in a swarm. To be fair, to be able to do so does seem like a divine act, even when we do understand the biology. While we know that its sort of triggered by serotonin, we don’t as far as I can tell, really know how that leads to massive changes in the body. But the changes are profound. Increased serotonin leads to more sex, their bodies increase in size, with less difference between sexes, and their metabolic rate increases. Like I said, orgy slash rave.

Many other insect species share some of the behaviours we saw in the Dictyostelium slime mould. The term eusociality is used in science to describe literally the highest level of organisation of sociality, and you see it swarms of bees, or colonies of ants. Scientists consider these groups to act as meta-organisms, organisms made up of many organisms.

It does of course beg the question, how do we know it doesn’t also apply to us? What if we have parts of our genes that get activated by certain environmental factors? How do we know we’re not just individuals inside a meta organism? Every one of our cells is a descendant of a single-celled organism. And we’re increasingly aware of the fact that most of our mass is other species living within us.

So, what about humans? Are we capable of plasticity? There is something to be said about epigenetics, new studies that show how trauma and environmental toxins quite literally reshape our gene expression within lifetimes. We could also talk about how much our genetics have been co-constructed by other species. Paleogeneticists have identified over a hundred separate events in the history of the human genome where we have incorporated genetics from retroviruses. Sometimes when they try to inject genetics into our cells to replicate themselves, the genetics just ends up becoming part of our own.

For example, we owe our ability to grow offspring in placenta to a retrovirus. The same protein-making process that prevents our immune system from fighting the virus is what prevents the person’s body from fighting the foetus.

All of this being true, I want to come back to my original definition of plasticity and recall that behaviour is a mark of plasticity too. And I think that perhaps the most plastic thing about us is our culture.

Thinking about what I was saying about finding ourselves in nature, do we, as gays and genderbenders need to use other species to justify our existence? I don’t feel like we do. The use of nature to justify the order of things is sometimes called the Natural Fallacy. Just because something’s found in other species, doesn’t mean it has to be the law of our lives. Plasticity also means our ability to make choices about what forms of sociality work for us!

However, I do think we need to listen to other species, to understand how they relate to themselves and each other. And our dominant culture is very clearly at a crossroads. Far from plastic, it feels concrete and brittle. Or perhaps stuck in the form of a cargo ship, unable to change course, headed full speed towards the hurricane. Our dominant culture, the wealthy forces funding the far right, is choosing to target diversity, talk of us as a threat to the nation, to the economy, to the family unit. And those same forces that seem terrified by human diversity are also very content to destroy non-human biodiversity. Different cultures, different uses of gender, different neurotypes and ways of processing information, different bodies, abilities, ways of approaching work and care. I feel that so much of this destructive hate we’re trying to navigate, grow through, as a species seems to be rooted in a fear, maybe a fear of plasticity. Fear that we could do things differently, if we chose to.

That’s not to say that survival needs to be plastic. We spoke about ginkgo, but Horsetails, Equisetum, have been around a bit longer and though we no longer see the tree-sized species, have scarcely changed in form. Its something that works

But unlike horsetails, our species does seem to be driving a major extinction event. And we have to make a choice about how we use our plasticity to relate to the rest of the living world. I believe we are able to make a choice, and break out of this separation thinking. When we talk about ecological thinking, we’re trying to go beyond binaries a bit, beyond right and wrong, good and bad, natural and unnatural. Instead we’re asking, what are the relationships that matter? How do we relate to other species and what ways can we deepen them? Is it symbiotic, or just destructive? Relations with the rest of the world matter, and we clearly need different approaches to living, between species and within our own species, to survive in this world. Look at the tree of life, a constant transformation of forms and ways of living, and yet all sharing a single common ancestor, LUCA. For all our separation, we are not outside of life, and that web of being is calling us to change.

So lets shape shift together. Let’s be beautifully plastic.